The symbolism is ancient, and I discuss it in All Things Made New. John himself is echoing Ezekiel's vision during the time of the Babylonian exile (1:10), and the image recalls the Babylonian sphinxes or composite creatures known as "cherubims". They also represent the four fixed signs of the Zodiac; that is, the four corners of the celestial cosmos: Aquarius the winged

Wednesday, 28 December 2011

Animals in heaven

The symbolism is ancient, and I discuss it in All Things Made New. John himself is echoing Ezekiel's vision during the time of the Babylonian exile (1:10), and the image recalls the Babylonian sphinxes or composite creatures known as "cherubims". They also represent the four fixed signs of the Zodiac; that is, the four corners of the celestial cosmos: Aquarius the winged

Sunday, 25 December 2011

"On earth as it is in heaven"

"The words of the Lord's Prayer point out the Father, the Father's name, and the Father's kingdom to help us learn from the source himself to honour, to invoke, and to adore the one Trinity. For the name of God the Father is the only-begotten Son, and the kingdom of God the Father is the Holy Spirit."If the "name" is the Son, then when the Lord tells Moses (Numbers 6: 22-7) to "call down my name on the sons of Israel" and bless them with the words, "May the Lord let his face shine on you and be gracious to you", he is instructing them

Wednesday, 21 December 2011

"Formed by divine teaching, we dare to say..."

In the new translation of the Roman Missal, the Lord's Prayer is introduced with the words, "At the Saviour's command and formed by divine teaching, we dare to say..." The prayer itself is so familiar to us that we often forget that it was given to the disciples in the context of a series of instructions about how to pray it. What is this teaching in which we have been "formed"?

In Matthew 6: 5-15 the Prayer is taught in the context of the Sermon on the Mount (chapters 5, 6, and 7), which concerns the various dimensions of the living of the Christian life, beginning with the Beatitudes which form the portrait of the perfect Christian. Immediately before the teaching on prayer, he speaks of the love of enemies and of almsgiving in secret. This leads him naturally to go on: "when you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you." This is the lead-in to the Lord's Prayer itself (6: 9-15), and it is paralleled by a passage at the end where he speaks of fasting: "when

Sunday, 18 December 2011

Dawn of the Real

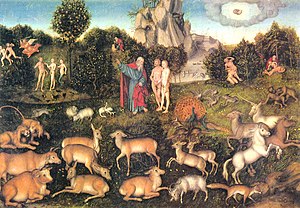

Schmemann tells us that the Eucharist is first of all a state of existence. "Eucharist, thanksgiving, is the state of the innocent man, the state of paradise. Before sin, man's life was eucharistic, for 'eucharist' is the only relationship between God and man which transcends and transforms man's created condition" (Liturgy and Tradition, p. 111). "Eucharist", therefore, is a state of being, a state of complete dependence lived as "love, thanksgiving, adoration", and this is true innocence and freedom.

Original sin, he goes on, was "the loss of that eucharistic state", of the blissfully real life we had in love and communion with God. The Old Testament is a record of failed attempts to recover this eucharistic state. In the end, of course, it was restored to us in Christ. "His whole life, and he himself, was a perfect Eucharist, a full and perfect offering to God. Thus the Eucharist was restored to man."

Labels:

Eucharist,

mystagogy,

Orthodox Church,

Schmemann

Friday, 16 December 2011

Seeking the face of God

The Genesis account of the Creation and Fall, poetic and metaphysical, takes place in an archetypal landscape that lies behind our world and shapes it from within. In that sense, while we are conscious of the state of fallen nature, into which we have been exiled – it is evident in the facts of death and suffering and the weakness of our will – the archetypal landscape of Genesis is not entirely inaccessible. Chesterton speculated that the garden of Eden lies all around us still, only our eyes have changed so we cannot see it. There are some of the English mystics who have "cleansed their eyes" and seen paradise: Thomas Traherne, William Blake, and Samuel Palmer were among them. Traherne wrote: "Your enjoyment of the world is never right, till every morning you awake

Monday, 12 December 2011

The eyes of faith

The first volume of Hans Urs von Balthasar’s The Glory of the Lord lays the foundation for a recovery of the lost art of reading "objective symbolism" and thus the deeper meanings of Scripture. In it the history of the tradition of the spiritual senses – faith as a "theological act of perception" – is thoroughly explored, and the importance of its recovery for our time is explained. The weakness of Christianity after the Enlightenment is due very largely to the distortions induced by rationalism, sentimentalism, moralism, and voluntarism. Balthasar writes (p. 140) that the integration of the act of perception back into our understanding of faith

"is not only of theological and theoretical interest; it is a vital question for Christianity today, which can only commend itself to the surrounding world if it first regards itself as being worthy of belief. And it will only do this if faith, for Christians, does not first and last mean 'holding certain propositions to be true' which are incomprehensible to human reason and must be accepted only out of obedience to authority."For a generation unwilling to accept the truths of faith on the authority of tradition or of the Church, there has to be an act of seeing into the words of Scripture and the events of history, which reveals not merely the logical consistency of a Creed,

Saturday, 10 December 2011

The language of the heart

If this intuitive vision or “depth-perception” has been neglected, if we are living only on the surface of our faith, if we have not been listening enough to our poets and visionaries, we will find, as we are finding now, that the faith our ancestors professed is easily dislodged as tumbleweed. It has no deep root in us, for we have not grasped its significance as the key to understanding the world – even

Tuesday, 6 December 2011

Sacred Signs

The little book Sacred Signs by Romano Guardini is a model for a kind of mystagogical catechesis that is sorely lacking in today's Church. In order to appreciate the sacraments and sacramentals, we need to see that they employ a symbolic language that has much wider applications. This can help us see the whole world in a different way, as linked together not just by the causality investigated by modern science, but by analogies and resemblances that add other layers of meaning, and which speak of the "vertical causation" by which God reveals himself in creation. The translator of the book, Grace Branham, in her excellent Preface writes:

'Guardini's "Sacred Signs" was designed to begin our reeducation. It assumes that correspondence between man and nature, matter and meaning, which is the basis of the Sacramental System and made possible the Incarnation. Man, body and soul together, is made in the image and likeness of God. His hand, like God's, is an instrument of power. In the Bible "hand" means power. Man's feet stand for

Thursday, 1 December 2011

The three stages of Christian life

As I said at the end of The Seven Sacraments, "mystagogy" is the stage of exploratory catechesis that comes after apologetics, after evangelization, and after the so-called "sacraments of initiation" (Baptism, Eucharist, and Confirmation) have been received. Baptism and Confirmation may be given only once. Christian initiation, however, is a continuing adventure, since the grace of these sacraments is the source of a new life of prayer that must continue to grow, if it is not to wither and die.

One of the greatest of Christian masters of mystagogy, who wrote under a pseudonym around five hundred years after the birth of Christ, is Dionysius the Areopagite, sometimes called Saint Denys. His influence on Christian mysticism, art, and architecture (through, for example, the school of Chartres in eleventh century France) has been immeasurable, his orthodoxy assured by such admirers and interpreters as Maximus the Confessor in the East and Thomas Aquinas in the West.

Dionysius divided the Christian Way into three phases, which he called purification, illumination and union, and linked these to the three hierarchies of angels, who were thought to assist in each of these three phases—to put it

One of the greatest of Christian masters of mystagogy, who wrote under a pseudonym around five hundred years after the birth of Christ, is Dionysius the Areopagite, sometimes called Saint Denys. His influence on Christian mysticism, art, and architecture (through, for example, the school of Chartres in eleventh century France) has been immeasurable, his orthodoxy assured by such admirers and interpreters as Maximus the Confessor in the East and Thomas Aquinas in the West.

Dionysius divided the Christian Way into three phases, which he called purification, illumination and union, and linked these to the three hierarchies of angels, who were thought to assist in each of these three phases—to put it

Friday, 25 November 2011

The Ascent to God

St Bonaventure’s Itinerarium Mentis in Deum or The Soul’s Journey Into God is based around the image of the six-winged Seraph seen by St Francis on the slopes of Mount Alverna; a vision that imprinted on him the living seal of the Stigmata. According to Isaiah, “each had six wings: with two he covered his face, and with two he covered his feet, and with two he flew” (6:2). This image may be considered a private revelation to Francis by one of the Seraphim, who presents him with an image of the Crucified that is also an intimation of the divinized form of Man, of Francis himself as the saint he will one day become, transformed by God’s grace.

According to Bonaventure’s interpretation, the two lower wings of the figure correspond to the human body, the second pair to the soul, and the third to the spirit. In several prophetic visions of the seraphim, their wings are covered in eyes to signify consciousness. Thus they represent three types of consciousness – as

According to Bonaventure’s interpretation, the two lower wings of the figure correspond to the human body, the second pair to the soul, and the third to the spirit. In several prophetic visions of the seraphim, their wings are covered in eyes to signify consciousness. Thus they represent three types of consciousness – as

Sunday, 20 November 2011

How "Made New"?

As I argue in All Things Made New, this is perhaps the key insight of Christianity – that the coming of Christ changes everything – which the Book of Revelation expresses in rich imaginative language, and the prayers of the Rosary celebrate and penetrate through repeated meditation. The "new" is not yet fully revealed. It is visible to the eyes of faith, and it walked the earth in the days before the Ascension of our Lord into heaven. It is the Resurrection, the world of matter and time made over again by the Creator, purified through death, losing nothing that is of value, and raised into the spiritual world.

Our life is hidden in Christ – that is, our new life, which grows in us as the old continues to pass away, until we find ourselves caught up in the flow of love between the Persons of the Trinity. But how do we know this to be so? People today are reluctant to believe things on "faith", but that is because they oppose faith to experience. "Give me experience and I will believe (if I choose)." In Hebrews 11:1, on the other hand, faith is defined as the "reality" or "substance" (hupostasis, meaning something or someone to be relied upon) of things hoped for, the proof of things not seen. Faith may operate in the dark, but when we do find ourselves in the dark we rely on other senses than sight, particularly hearing and touch. This is perhaps the best analogy. Faith is a supernatural gift akin to the opening of a new sense, enabling us to hold on to a truth that our bodily eyes are simply not yet suited to grasp.

The Book of Revelation is a translation into visual images and symbolic language of the truths grasped by faith. John knows that creation in its entirety has always been ordered towards the Incarnation. Its order and intelligibility are due not to its being a pale imitation of the One, but to the presence within it of the God-Man. This presence is brought about by an action, by God’s willing to give himself both in eternity and in time – and the latter intention necessitates the creation. The universe is grounded in the freedom of love. The wellspring of this Johnannine tradition, that flows down through the Letters and Revelation through to mystical writers such as Dionysius and Eriugena, is to be found in the Prologue to John's Gospel and the Farewell Discourses, where Jesus speaks of the overcoming of the world and his own glorification, the indwelling of the Son in the Father and of the believers in the Trinity.

John Scotus Eriugena describes faith using another metaphor, based on Jesus's words in Scripture. Faith is a seed, like a mustard seed, "a certain principle from which knowledge of the Creator begins to emerge in rational nature." Faith is not an alternative to knowledge, but the beginning of a certain mystical knowledge or experience of God, which leads to him as it matures. It is the awakening of the supernatural life of the soul, the seed of the fruit of the Word. See his commentary on the Prologue in The Voice of the Eagle.

(Readers may also be interested in the very fine philosophical and textual commentary The Beginning of the Gospel of John by James R. Mensch, which is available online minus the Greek.)

Friday, 18 November 2011

Lectio Divina

One of the greatest gifts of St Benedict to our civilization was the daily practice of lectio divina or "spiritual reading", which has now spread from the monasteries to enrich the whole Church. The basic steps are outlined in Verbum Domini. Lectio divina is an attentive and reflective pondering of sacred scripture, so that it becomes prayer (CCC, 1177). It enables the believer to “hear God’s Word as it speaks to us, ever personally, here and now” (Pope Benedict). Magnificat has been running a series of lectio meditations each month, and the following example is taken from the November 2011 issue. It is a reflection on Matthew 25: 14-30.

Wednesday, 16 November 2011

Mysteries of the Rosary

The Rosary is a very "metaphysical" prayer. Mary is like the primordial waters lying open before the life-giving action of God at the beginning of the world. By praying we are trying to become like her, receptive to the will of God. Mary’s fiat ("Let it be to me according to your word") echoes God’s fiat ("Let there be light") in the very beginning of creation, and her Son’s fiat ("Let not my will but thine be done") in the Garden of Gethsemane (Luke 22: 42).

The five Joyful, five Sorrowful and five Glorious mysteries describe the life of human childhood, the adult life and the supernatural life. Taken as applying to the individual soul they describe, first, the life of the soul as it opens itself to grace, second as it struggles to follow Christ, and finally as it experiences the transformation wrought by grace. Blessed John Paul II introduced a further set of five "Luminous" mysteries to be prayed between the Joyful and the Sorrowful. These summarize Christ’s public ministry between his Baptism and his Passion (the Baptism in the Jordan, the Miracle at Cana, the Preaching of the Kingdom, the Transfiguration, and the Eucharist).

Ancient and medieval thinkers found symbolic significance in numerical patterns. The Apostles’ Creed through which one enters the Rosary has twelve sections, like the gates of the New Jerusalem. The Lord’s Prayer which begins each sequence has seven, like the seven sacraments or the seven days of creation. The Glory Be with which each sequence ends is Trinitarian. Each sequence of beads is made up of ten Hail Marys, ten being the sum of seven and three, itself symbolic of the expansion of the totality of numbers contained in One. A Rosary contains five mysteries, five being the number of life and growth, found especially in flowers and leaves. (Five is also closely related to the Golden Ratio and thus to many aspects of beauty in nature.)

By the addition of the five Luminous Mysteries, bringing the number of rosaries to four, Pope John Paul II seems to have brought the ancient tradition to its completion. The fourfold structure of the Mysteries recalls the fourfold Gospels, and each of the four sets of Mysteries corresponds to one of the Gospels in a special way. The Joyful Mysteries correspond to the Gospel of Matthew, whose symbol is a Man and who emphasizes the titles “Son of Man”, “Son of Abraham”, “Son of David”. The Sorrowful correspond to Luke, whose symbol is the Ox and whose Gospel emphasizes the role of Jesus as sacrificial victim. The Luminous would then correspond with Mark, whose symbol is the Lion, and who proclaims the divine power of the Lord. Finally the Glorious Mysteries can be associated with John, whose symbol is the Eagle, and who teaches us the most about the intimate relationship between the Son and his heavenly Father.

Tuesday, 15 November 2011

How to read the Bible

So longs my soul for Christ, the Well:

From him, the living waters flow

Through wastes where withered spirits dwell.

These lines from a popular hymn evoke the picture in the title of this blog, which is a detail from the ceiling above the shrine of Our Lady of Oxford. They express the yearning for living waters that we feel as we approach Sacred Scripture. A rich discussion by Adrian Walker of Scripture as "living water" especially in the thought of Benedict XVI was published in Second Spring and Communio and may be found online here.

In All Things Made New I provide a summary of the current state of Biblical scholarship, which is in the process of outgrowing an obsession with historical-critical interpretation. In the Middle Ages it was commonplace to speak of the four

Monday, 14 November 2011

The Unveiling

The Apocalypse ("Unveiling") has long been a challenge to exegetes. In fact it is one of the most mysterious works of the inspired imagination known to humanity. It is more than a vision of the End Times, with the great battles and judgments depicted in paintings throughout the Middle Ages. It is a vision of the underlying structures of the cosmos, and the reality of the spiritual life. The City that descends out of heaven in the final chapters of that great book is the City of the human soul, redeemed and purified, and of the community of eternals – a human and angelic society that is the goal and fulfilment of history. Permeated with

John and Mary

In the next few posts, I want to reflect on some elements in the book All Things Made New. I have already situated it in the context of mystagogy, or the attempt to penetrate more deeply into the richness of Christian teachings for the sake of truer conversion. The blurb explains that "The shattering impact of the Incarnation was felt first by the Mother of Jesus and by his closest disciples. Its meaning was best understood by Mary as she pondered these things in her heart, and the beloved disciple, John, who took her into his home. Mary and John at the foot of the Cross are witnesses and teachers of the mystery of God’s love." Thus

Is Christianity Esoteric?

“For He was sent not only to be known but also to remain hidden” – Origen.

The term “esotericism” dates from the nineteenth century (along with “mysticism” and “occultism”). In his book Guenonian Esoterism and Christian Mystery, Jean Borella describes it as a form of hermeneutic “apt for the opening of our consciousness to the presence of the Spirit hidden in revealed forms and sometimes under the appearance of the most baffling symbols,” developed for an age in which the sense for symbolism and tradition has long been in retreat – relating this also to Saint Paul’s contrast between the letter and the spirit, and the mystagogical catechesis of the Alexandrian Church Fathers.

Strictly speaking, there is no Esoteric Christianity, in the sense of a secret teaching different from that which you will find in the Catechism and known only by a inner ring or elite, because Christianity by its nature dissolves boundaries like that. It is itself a kind of Esoteric Judaism turned inside out and offered to the world. There is something bizarre about this. It is pearls cast before swine, riches trampled in the mire. Jesus talks of this in the parable of the Wedding Banquet, where the Lord in the story drags the hedgerows and street corners for riff-raff to fill his table, the honoured guests having declined to attend.

There is no Esoteric Christianity; there is, however, a Christian Esoterism. (See longer article.) Anyone can pick up a pearl, but only a few know what to do with it. "Even so truly a ‘church of the people’ as the Catholic Church does not abolish genuine esotericism. The secret path of the saints is never denied to one who is really willing to follow it. But who in the crowd troubles himself over such a path?" – Hans Urs von Balthasar.

Strictly speaking, there is no Esoteric Christianity, in the sense of a secret teaching different from that which you will find in the Catechism and known only by a inner ring or elite, because Christianity by its nature dissolves boundaries like that. It is itself a kind of Esoteric Judaism turned inside out and offered to the world. There is something bizarre about this. It is pearls cast before swine, riches trampled in the mire. Jesus talks of this in the parable of the Wedding Banquet, where the Lord in the story drags the hedgerows and street corners for riff-raff to fill his table, the honoured guests having declined to attend.

There is no Esoteric Christianity; there is, however, a Christian Esoterism. (See longer article.) Anyone can pick up a pearl, but only a few know what to do with it. "Even so truly a ‘church of the people’ as the Catholic Church does not abolish genuine esotericism. The secret path of the saints is never denied to one who is really willing to follow it. But who in the crowd troubles himself over such a path?" – Hans Urs von Balthasar.

Friday, 11 November 2011

Jean Borella

“Having set out in search of the secret of Charity, one day I ‘encountered’ Trinitarian theology… I went back to ancient doctrines like a delighted child going from discovery to discovery, from treasure to treasure, from marvel to marvel…. Drinking in the freshness of the ages, I felt my Christian soul revive. Henceforth it was impossible to repudiate the source of our faith, impossible not to offer it to drink.” (Jean Borella, The Secret of the Christian Way, p. 3.)An important reference-point for today's revival of metaphysical Christianity is the work of Jean Borella, a Catholic Traditionalist who has in recent years distanced himself from Frithjof Schuon, having concluded that both Schuon and Guénon had failed to understand some crucial elements of the Christian tradition (as

Labels:

Borella,

deification,

metaphysics,

Schuon

Thursday, 10 November 2011

Trinitarian Man

What is man? For Descartes, and for most of us unconsciously, man is a compound of body and soul; that is, a body and various mental states and faculties uneasily stitched together. But the traditional conception of man is rather more sophisticated, and needs to be recovered. We see a reference to it in St Paul’s first letter to the Thessalonians (5:23): “spirit and soul and body”.

Cardinal Henri de Lubac devoted a long essay to the development and subsequent neglect of Pauline tripartite anthropology in the Christian West (it can be found in the volume Theology in History, published by Ignatius Press in 1996).

Labels:

anthropology,

history,

human nature,

Trinity

Tuesday, 8 November 2011

Spirit of Assisi

Religious differences as a factor in social violence has become a familiar theme, and one which the New Atheists make much of. In October at Assisi, the Pope invited to a gathering of religious believers a number of agnostics, led by Julia Kristeva – people “people to whom the gift of faith has not been given, but who are nevertheless on the lookout for truth, searching for God.” He saw that such seekers are the true allies of the faithful. They seek truth and goodness. They are “pilgrims of truth, pilgrims of peace.” “They ask questions of both sides,” never giving up hope in “the existence of truth and in the possibility and necessity of living by it.” But they will not settle easily and blindly into faith. They challenge the followers of religions “not to consider God as their own property, as if he belonged to them, in such a way that they feel vindicated in using force against others.” This is the critique we need, for believers have done more harm than good by their attempts to manipulate others into faith. Once again, we see the importance of keeping faith in harmony with reason, because it is unreasonable to trust hypocrites. Unfortunately, physical violence in the name of faith is only the tip of the iceberg: violence begins with judgment and rejection, fear and resentment, anger and pride. The path to peace is the path of prayer and opening to grace, which alone can renew the face of the earth.

For an interesting article on the Pope's approach to inter-religious and inter-cultural dialogue, by Gabriel Richi-Alberti of Oasis, go here.

For an interesting article on the Pope's approach to inter-religious and inter-cultural dialogue, by Gabriel Richi-Alberti of Oasis, go here.

Friday, 4 November 2011

The Lord's Prayer

In my new book (see below) I include a commentary on the Lord’s Prayer, and in The Seven Sacraments (on the right) I tried to show how the seven petitions of the Prayer correspond to other patterns of seven in the Christian tradition, and to the needs of the human heart. But there is always more to say about this Prayer, so deceptively simple and yet profound. One of the most fascinating and richest expositions I have ever seen is G. John Champoux’s The Way to Our Heavenly Father, which shows how the whole of Scripture and all the spiritual teachings of the Fathers can be organized and correlated with the various parts of the Prayer, as though before our eyes the entire Christian revelation was flowering and refolding back into the one Prayer. The collection consists not of detailed commentary (although there are

Thursday, 27 October 2011

Announcement

This is the book after which this blog is named. You can order it from Amazon US, or Amazon UK, or through your local bookshop, or the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-59731-129-8. The spectacular cover art is by Daniel Mitsui. (Go to his web-site for a detailed view.) Review copies of All Things Made New can be requested from the publisher at Angelico Press, John Riess (jriess718@gmail.com).

All Things Made New explores the Christian mysteries by studying the symbolism, cosmology, and meaning firstly of the Book of Revelation (reading this as a prophetic and mystical commentary on the Divine Liturgy rather than a set of predictions) and secondly of the prayers and meditations of the Rosary, including the Apostles’ Creed and the Our Father.

Why put these together in one book? The shattering impact of the Incarnation was felt first by the Mother of Jesus and by his closest disciples. Its meaning was best understood by Mary as she pondered these things in her heart, and the beloved disciple, John, who took her into his home. Mary and John at the foot of the Cross, depicted on the cover by Daniel Mitsui, are witnesses and teachers of the mystery of God’s love. So the book attempts to explore the Christian Mysteries as much as possible "through the eyes" on John and Mary, with the help of the Book of Revelation and the Rosary.

I have run a series of posts discussing aspects and themes of the book that may be of interest to potential readers. The series runs in order as follows: Mystagogy, John and Mary, The Unveiling, How to read the Bible, Mysteries of the Rosary, How "Made New"? The series then continues through November and December 2011.

Readers interested in Mystagogy might like to know that All Things Made New forms a sequel to The Seven Sacraments: Entering the Mysteries of God. That earlier book, in turn, has been thoroughly revised, and will be republished in a new edition by Crossroad in due course.

To go to the Home Page of this blog click here or on the main title bar above.

All Things Made New explores the Christian mysteries by studying the symbolism, cosmology, and meaning firstly of the Book of Revelation (reading this as a prophetic and mystical commentary on the Divine Liturgy rather than a set of predictions) and secondly of the prayers and meditations of the Rosary, including the Apostles’ Creed and the Our Father.

Why put these together in one book? The shattering impact of the Incarnation was felt first by the Mother of Jesus and by his closest disciples. Its meaning was best understood by Mary as she pondered these things in her heart, and the beloved disciple, John, who took her into his home. Mary and John at the foot of the Cross, depicted on the cover by Daniel Mitsui, are witnesses and teachers of the mystery of God’s love. So the book attempts to explore the Christian Mysteries as much as possible "through the eyes" on John and Mary, with the help of the Book of Revelation and the Rosary.

I have run a series of posts discussing aspects and themes of the book that may be of interest to potential readers. The series runs in order as follows: Mystagogy, John and Mary, The Unveiling, How to read the Bible, Mysteries of the Rosary, How "Made New"? The series then continues through November and December 2011.

Readers interested in Mystagogy might like to know that All Things Made New forms a sequel to The Seven Sacraments: Entering the Mysteries of God. That earlier book, in turn, has been thoroughly revised, and will be republished in a new edition by Crossroad in due course.

To go to the Home Page of this blog click here or on the main title bar above.

Thursday, 22 September 2011

Faith, reason, and imagination

The French poet Paul Claudel once wrote:

"The evil we have been suffering from for several centuries is less a split between Faith and Reason than between Faith and an Imagination become incapable of establishing an accord between the two parts of the universe, the visible and the invisible."The quotation comes from an excellent article on Claudel by Michael Donley in the Temenos Academy Review for 2005 (p. 45). How might this thought be expanded? What is the role of the Imagination?

The imaginative faculty mediates between the sensory and the intellectual world in its own way just as the reasoning faculty does. But like all mediators it is ambiguous. It has two sides or faces, depending in this case on its relationship to the higher spiritual faculty. When the imagination faces "upwards" towards the archetypes of reality, assisted by the active imagination, it is capable of mediating and transmitting truth, as it does in the true visions received by prophets, and also in the works

Thursday, 1 September 2011

The new Missal translation

We have been explaining the changes in Magnificat month by month. One of the most obvious is in the greeting at Mass. The Priest says, "The Lord be with you," and we no longer respond, "And also with you," but, "And with your spirit" (which is exactly what the Latin says: "Et cum spiritu tuo"). What does it mean? As Lawrence Lew explained in the June issue of Magnificat, the expression comes from Saint Paul (cf. Ga 6: 18; Ph 4: 23; 2 Tm 4: 22), and is linked with the greeting from Ruth 2: 4. the “spirit” refers to the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, specifically here with reference to the ordained who “performs the sacrifice in the power of the Holy Spirit”. In a sense, we are praying in charity that our priest might abide in the Spirit. A prayer always needed, and never more than today when priesthood is under such attack.

For Anthony Esolen's commentary for Magnificat on the poetry of the new translation, see Zenit or First Things.

Friday, 29 July 2011

Theology of the body

An old friend of mine (and long ago of Charles Williams), Lois Lang-Sims, recently said that “All these teachings about sex and about the sanctity of human life and the human body have their roots in metaphysics,” which, she added, is the last thing anyone these days wants to talk about. Pope John Paul II understood this and called for a renewal of metaphysics in his encyclical Fides et Ratio. The key to his Theology of the Body seems to me this:

Since I posted this item, a brilliant interview on the subject has appeared with Bishop Jean Lafitte. And if anyone wants to study the subject in depth, the best book-length introduction I know is Called to Love, by Anderson and Granados. I will return to this subject on another occasion.

“The body, in fact, and only the body, is capable of making visible what is invisible: the spiritual and the divine. It has been created to transfer into the visible reality of the world the mystery hidden from eternity in God, and thus to be a sign of it.” – John Paul II, 20 February 1980, General AudienceThe same Pope talks about the “spousal” or “nuptial” meaning of the body, which he says is “not something merely conceptual” but concerns a “way of living the body” in its masculinity and femininity, an “inner dimension… that stands at the root of all facts that constitute man’s history”. This nuptial meaning has been limited, violated and deformed over time and by modern culture, until we have almost lost the power of “seeing” it, but it is still there to be discovered with the help of grace, like a spark deep within the human heart. The “language of the body”, therefore, must be recovered, and that is what the Pope seeks to do. But as he says, correctly reading this “language” results not so much in a set of statements as in a “way of living”.

Since I posted this item, a brilliant interview on the subject has appeared with Bishop Jean Lafitte. And if anyone wants to study the subject in depth, the best book-length introduction I know is Called to Love, by Anderson and Granados. I will return to this subject on another occasion.

Saturday, 16 July 2011

Hortus Conclusus

The medieval mystics loved to meditate on the Virgin Mary as the “enclosed garden” or “walled garden” of the Song of Songs, and as the new “Garden of Eden”, Paradise restored. St Bernard of Clairvaux is frequently cited – as here, by St John Eudes in The Admirable Heart of Mary (Loreto Publications, 2004, 70):

The tradition of the hortus conclusus is entwined with that of the Immaculate Conception, because just as Adam was made from the earth before the Fall, so it seemed eminently fitting that the second Adam should be made from a woman similarly untouched by sin. God was making a new beginning for the human race. In order to plant the new Tree of Life, he had to establish around it an enclosed garden, protected from the corruption of the world outside. That garden was Mary.

Thou art an enclosed garden, O Mother of God, wherein we cull all kinds of flowers. Among them, we gaze with particular admiration on thy violets, thy lilies, and thy roses, which fill the House of God with their sweet fragrance. Thou art, O Mary, a violet of humility, a lily of chastity, and a rose of charity.”In the original Garden, St John comments, man hid from God and God had to call for him. In the new Garden, the second Paradise, God hid himself and his glory for love, so that the three kings who came from afar had to ask, “Where is he?”

The tradition of the hortus conclusus is entwined with that of the Immaculate Conception, because just as Adam was made from the earth before the Fall, so it seemed eminently fitting that the second Adam should be made from a woman similarly untouched by sin. God was making a new beginning for the human race. In order to plant the new Tree of Life, he had to establish around it an enclosed garden, protected from the corruption of the world outside. That garden was Mary.

Monday, 11 July 2011

More on offering

I think we are too quick to think in terms of rules in both the moral and spiritual life (which are really the same thing), without realizing what those rules really mean. There is a rule, for instance, about going to confession before receiving communion if we are in a state of serious sin, and lots of lists of what sins are "serious". But the point is surely that the spiritual effect of communion depends on the quality of our self-gift. When the priest prepares the offerings at the altar, we are attempting to join ourselves to those gifts, so that the self we give to God in them can given back to us transformed. In receiving communion we receive into ourselves not just the host, but Christ himself, and in him the new self that he is wanting us to become. But sin is always a form of attachment to the old self. Thus if we are in a state of sin before Mass we are in a state of attachment, of holding back part of ourselves from the gift - and this part of ourselves cannot be transformed. Going to confession is a way - the best way, sometimes the only way - of detaching ourselves from ourselves, so as to benefit from the Mass.

Friday, 10 June 2011

Forgiveness

“Forgiveness does not mean that God says to me: Your evil deed shall be undone. It was done and remains done. Nor does it mean that he says: It was not so bad. It was bad – I know it and God knows it. And again it does not mean that God is willing to cover up my sin or to look the other way. What help would that be? I want to be rid of my transgression, really rid of it….”

This is a quotation from Romano Guardini (one of the excellent daily spiritual meditations in the monthly publication Magnificat, in this case scheduled for the Sept 2011 issue, pp. 142-3). Guardini continues: “What possibility then does exist? Only one: that which the simplest interpretation of the Gospel suggests and which the believing heart must feel. Through God’s forgiveness, in the eyes of his sacred truth I am no longer a sinner; in the profoundest depths of my conscience I am no longer guilty.”

“I am no longer a sinner,” although the sin remains. What does that mean? That the “I” has changed. I am no longer the person who committed that sin. That person has been detached from me, stripped off, and washed away. I am a new person, though I include everything that was good and worthwhile in the old – even the wounds left by sin have now become my trophies and emblems. Only God can bring about such a new birth, such a resurrection, such a “new earth”.

This is a quotation from Romano Guardini (one of the excellent daily spiritual meditations in the monthly publication Magnificat, in this case scheduled for the Sept 2011 issue, pp. 142-3). Guardini continues: “What possibility then does exist? Only one: that which the simplest interpretation of the Gospel suggests and which the believing heart must feel. Through God’s forgiveness, in the eyes of his sacred truth I am no longer a sinner; in the profoundest depths of my conscience I am no longer guilty.”

“I am no longer a sinner,” although the sin remains. What does that mean? That the “I” has changed. I am no longer the person who committed that sin. That person has been detached from me, stripped off, and washed away. I am a new person, though I include everything that was good and worthwhile in the old – even the wounds left by sin have now become my trophies and emblems. Only God can bring about such a new birth, such a resurrection, such a “new earth”.

Monday, 6 June 2011

The spiritual machine

I was speaking with someone who has lost heart because going to Mass seems to do nothing for him. There is no spiritual experience involved, so that he is just going through the motions. It increasingly feels like a waste of time, if not actual hypocrisy. The answer to this problem, I think, lies in how we participate. The Mass is the greatest-ever work of "spiritual engineering". Like a suspension bridge over some huge chasm, or a giant piece of machinery, it is intended to do something. But in order for it to do its work, you need to cooperate or participate. You do have to walk over the bridge, or turn the machine on. Most of the time we don't do that: we just watch. The only way to participate is to give ourselves spiritually - that is, in our will, or intention - to the action of the Mass. The Liturgy of the Word at the beginning of Mass, with the act of contrition and the reading of Scripture, is designed to prepare us to do that. The actual giving takes place in the Offertory, when we add our hearts to the sacrifice. The first part is like a kind of "melting" of our hard hearts, which are frozen in a particular configuration, a particular shape. We are supposed to then "pour ourselves" into the Mass, just like molten metal is poured from a crucible into a mould, where it can be set into a new shape. But this is harder than it sounds. We tend to want to hold at least part of ourselves back. We are afraid of changing, or we are attached to something we don't want to let go of, which we can't give to God. That is the struggle, and it is that which makes Mass interesting. But to the extent - even if it is a limited extent - that we manage to let go and to give something of ourselves to God, he is able to do something with it, and we will immediately start to feel something very definite, something subtle but unmistakeable, which confirms to us that the process is happening.

Monday, 30 May 2011

Giving it "up"

|

| A scene from Leonie Caldecott's "The Quality of Mercy" |

We sacrifice something good, or enjoyable – we give it up – not as a punishment for sin, and not merely to demonstrate our obedience, but in order to obtain something better. Or rather, to make room in ourselves for something better that we hope for. Why get rid of something? To make room for something else. We give up food, or sleep, or sex, for the sake of something better – a sense of divine presence, or a more intimate union with God. We give up bad company in order to find good company. Naturally, as soon as we stop believing in that better thing, or its possibility, sacrifice will stop making sense to us.

It should be easy enough to explain, because this principle works in everyday life without any reference to religion at all. I give up snacks for the sake of slimming, I give up a lazy afternoon in order to exercise, I give up my favourite TV programme in order to spend time with someone who needs me. This implies that there are some goods and pleasures – feeling healthy, seeing a friend – that are qualitatively better, “higher”, than others. Extend the principle to include goods that are better yet, and types of happiness even more powerful and refined, and the notion of religious sacrifice suddenly makes perfect sense.

As we kneel at Mass, giving ourselves to God by identifying with the bread and wine that the priest is about to offer on the altar, we are emptying ourselves in order to receive a new self, the life of Christ which he pours out for us on the Cross and in the sacraments.

Thursday, 26 May 2011

Liturgical changes

The ongoing "reform of the reform" of the Catholic liturgy seems to be leading towards an interesting goal. As readers may know, the Old Rite has in the last few years been made once again widely available, and the New Rite promulgated by Paul VI after Vatican II is receiving a facelift, in the form of the new English translation of the Missal to be phased in from September. But Cardinal Kurt Koch recently let slip that “The Pope’s long-term aim is not simply to allow the old and new rites to co-exist, but to move toward a ‘common rite’ that is shaped by the mutual enrichment of the two Mass forms.” This did seem to be the implication of Cardinal Ratzinger's comments years ago at a conference I attended in Fontgombault. My own paper from that conference is available here.

Meanwhile, back to the facelift. We are running a series of articles on this in Magnificat (US and UK editions have different articles), and of course the new Mass texts will be available each month in Magnificat as needed. Elsewhere I recently ventured some thoughts of my own on one of the changes. The words by which the bread is consecrated remain pretty much the same as before: “Take this, all of you, and eat of it, for this is my Body, which will be given up for you.” But the words spoken over the wine are changed. They were previously: “Take this, all of you, and drink from it: this is the cup of my blood, the blood of the new and everlasting covenant. It will be shed for you and for all so that sins may be forgiven. Do this in memory of me.” Those are the familiar words, but now they read, in the revised translation: “Take this, all of you, and drink from it, for this is the chalice of my Blood, the Blood of the new and eternal covenant, which will be poured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins. Do this in memory of me.”

In the new version, the words “for many” replace “for all”. This is done on the grounds that

Meanwhile, back to the facelift. We are running a series of articles on this in Magnificat (US and UK editions have different articles), and of course the new Mass texts will be available each month in Magnificat as needed. Elsewhere I recently ventured some thoughts of my own on one of the changes. The words by which the bread is consecrated remain pretty much the same as before: “Take this, all of you, and eat of it, for this is my Body, which will be given up for you.” But the words spoken over the wine are changed. They were previously: “Take this, all of you, and drink from it: this is the cup of my blood, the blood of the new and everlasting covenant. It will be shed for you and for all so that sins may be forgiven. Do this in memory of me.” Those are the familiar words, but now they read, in the revised translation: “Take this, all of you, and drink from it, for this is the chalice of my Blood, the Blood of the new and eternal covenant, which will be poured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins. Do this in memory of me.”

In the new version, the words “for many” replace “for all”. This is done on the grounds that

Sunday, 15 May 2011

Detachment

When I was briefly with a Tibetan teacher, Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, I was shown a form of Dzogchen meditation that involved allowing thoughts and feelings and images in the soul to come and go. The essential thing was to allow them to flow without following them, without identifying with them as we normally do. In this way we penetrate to a deeper level of the self – Buddhists might say beyond the self altogether. Our usual state is one in which we identify with the flow of our thoughts, and create a false self that is mightily invested in things that don’t last. Let go of that, and you can allow yourself just to “be” without knowing who or what you are (a “feather on the breath of God”, as Hildegard says). After all – from a Christian point of view – only God knows us anyway.

Christians often criticize Buddhists for being turned inward on themselves, introverted, passive in the face of evil and suffering. Buddhists reciprocate by seeing Christians in flight from interiority, losing themselves in outward show and a well-intentioned activism (rooted in the false self and its judgments) that only makes the world a worse place. Yet the inward and the outward, contemplation and action, are not necessarily in opposition. The Buddhist is seeking a reality that lies beyond the false self. The Christian believes we become our true selves by doing what God gives us to do. Buddhist detachment closely resembles complete abandonment to God and his providence.

The statements of many Christian and Buddhist mystics can sound very much alike. Of course, Christians refer to God, whereas Buddhists do not. But, again, the “God” that Buddhists deny is a false God, just as the self they deny is a false self. In each case it is an idol we have fashioned for ourselves. “We will know God to the extent that we are set free from ourselves.” That was said by Pope Benedict XVI (see Magnificat, August 2011, p. 384). And Catherine of Siena (cited on p. 44 of the same issue of Magnificat) writes: “We rejoice and are content with whatever God permits: sickness or poverty, insult or abuse, intolerable or unreasonable commands. We rejoice and are glad in everything, and we see that God permits these things for our profit and perfection. I’m not surprised that we are, then, free from suffering, since we have shed the cause of suffering – I mean self-will grounded in self-centredness – and have put on God’s will grounded in charity.”

Catherine would probably say the Buddhist has “shed the cause of suffering” but has not yet “put on God’s will grounded in charity”. Pity and compassion, which Buddhism possesses in abundance, are not the same as love, which is directed towards the affirmation of the true self, not the dissolution of the false. Henri de Lubac SJ, in his excellent study, Aspects of Buddhism (1953), writes that without the fullness of charity, no one will ever realize the "void" of detachment. Buddhism lacks this fullness; it can take you only half way. But this should not cause the Christian feel superior to the Buddhist. Smugness would be a sign that the Christian has not yet achieved even the first half of his journey. And can we really say the second half is only open to those who possess the relevant conceptual apparatus?

Christians often criticize Buddhists for being turned inward on themselves, introverted, passive in the face of evil and suffering. Buddhists reciprocate by seeing Christians in flight from interiority, losing themselves in outward show and a well-intentioned activism (rooted in the false self and its judgments) that only makes the world a worse place. Yet the inward and the outward, contemplation and action, are not necessarily in opposition. The Buddhist is seeking a reality that lies beyond the false self. The Christian believes we become our true selves by doing what God gives us to do. Buddhist detachment closely resembles complete abandonment to God and his providence.

The statements of many Christian and Buddhist mystics can sound very much alike. Of course, Christians refer to God, whereas Buddhists do not. But, again, the “God” that Buddhists deny is a false God, just as the self they deny is a false self. In each case it is an idol we have fashioned for ourselves. “We will know God to the extent that we are set free from ourselves.” That was said by Pope Benedict XVI (see Magnificat, August 2011, p. 384). And Catherine of Siena (cited on p. 44 of the same issue of Magnificat) writes: “We rejoice and are content with whatever God permits: sickness or poverty, insult or abuse, intolerable or unreasonable commands. We rejoice and are glad in everything, and we see that God permits these things for our profit and perfection. I’m not surprised that we are, then, free from suffering, since we have shed the cause of suffering – I mean self-will grounded in self-centredness – and have put on God’s will grounded in charity.”

Catherine would probably say the Buddhist has “shed the cause of suffering” but has not yet “put on God’s will grounded in charity”. Pity and compassion, which Buddhism possesses in abundance, are not the same as love, which is directed towards the affirmation of the true self, not the dissolution of the false. Henri de Lubac SJ, in his excellent study, Aspects of Buddhism (1953), writes that without the fullness of charity, no one will ever realize the "void" of detachment. Buddhism lacks this fullness; it can take you only half way. But this should not cause the Christian feel superior to the Buddhist. Smugness would be a sign that the Christian has not yet achieved even the first half of his journey. And can we really say the second half is only open to those who possess the relevant conceptual apparatus?

Wednesday, 11 May 2011

Meister Eckhart

The German mystic Meister Eckhart is often viewed with suspicion by orthodox Catholics, and cited with approval by those who think he overcame the limitations of Christian dogma and made common cause with his fellow mystics in other religions.

The reason why Eckhart often reads like a heretic is that he was concerned to express not our own knowledge as individual creatures, but the divine knowledge itself, basing himself in the “ground” of the soul. As he says, “only in the ground of the soul is God known as he is,” for there “the intellect knows as it were within the Trinity and without otherness”. This possibility of knowing God “as God knows God” is opened to man by the Hypostatic Union of divine and human natures in Christ. C.F. Kelley’s Meister Eckhart on Divine Knowledge (Yale University Press, 1977) is a masterly study of exactly this point. As Kelley explains:

Kelley’s exposition hinges instead on esse or Being, which he translates as isness, the “act or isness of pure knowledge itself, or Godhead”, the “all-inclusive Reality” (p. 42). He even cites Dionysius in support of Eckhart: “We apply the titles of ‘Trinity’ and ‘Unity’ to that which is beyond all titles, designating under the form of Being that which is beyond Being” (p. 30). Kelley means by all this that the Trinity is not, as Schuon would say, simply the “prefiguration of Manifestation in the Principle”, or the relatively Absolute which stands at the summit of Maya, but is itself the unconditioned Absolute about which “nothing can be said” – save what God authorizes us to say. I have written further about this in "Trinity and Creation: An Eckhartian Perspective".

Also recommended is Cyprian Smith OSB, The Way of Paradox (DLT) and Commentaries on Meister Eckhart Sermons by Sylvester Houedard OSB.

The reason why Eckhart often reads like a heretic is that he was concerned to express not our own knowledge as individual creatures, but the divine knowledge itself, basing himself in the “ground” of the soul. As he says, “only in the ground of the soul is God known as he is,” for there “the intellect knows as it were within the Trinity and without otherness”. This possibility of knowing God “as God knows God” is opened to man by the Hypostatic Union of divine and human natures in Christ. C.F. Kelley’s Meister Eckhart on Divine Knowledge (Yale University Press, 1977) is a masterly study of exactly this point. As Kelley explains:

“A genuine understanding of the principial mode, which is constituted as it were within Godhead, is an understanding of truth that is beyond the potentiality of human cognition, restricted as that cognition is to individuality. Insight into this truth is a possibility only by way of transcendent act, never by way of potentiality. Yet the revelation of the Word is that transcendent act as assented to by the intellect when moved by the detached will to know.”When the perennialist Alvin Moore Jr reviewed Kelley’s book some years ago in Studies in Comparative Religion, he noted with stern disapproval the fact that Kelley (in Eckhart’s name) “equates the Godhead with the Trinity, sachchidananda with nirguna Brahman.” This goes to the heart of the matter. Kelley refuses, in his interpretation of Eckhart, to follow Schuon’s distinction between Being and Beyond-Being (that is, between the “relatively” Absolute and the “absolute” Absolute, thus relegating the Trinity to a subordinate status), or the related distinction between form and substance in the religions which underpins The Transcendent Unity of Religions.

Kelley’s exposition hinges instead on esse or Being, which he translates as isness, the “act or isness of pure knowledge itself, or Godhead”, the “all-inclusive Reality” (p. 42). He even cites Dionysius in support of Eckhart: “We apply the titles of ‘Trinity’ and ‘Unity’ to that which is beyond all titles, designating under the form of Being that which is beyond Being” (p. 30). Kelley means by all this that the Trinity is not, as Schuon would say, simply the “prefiguration of Manifestation in the Principle”, or the relatively Absolute which stands at the summit of Maya, but is itself the unconditioned Absolute about which “nothing can be said” – save what God authorizes us to say. I have written further about this in "Trinity and Creation: An Eckhartian Perspective".

Also recommended is Cyprian Smith OSB, The Way of Paradox (DLT) and Commentaries on Meister Eckhart Sermons by Sylvester Houedard OSB.

Thursday, 5 May 2011

Christian non-dualism

Two men and a bird...? Images of the Trinity are not uncommon in Christian art, but they have all to be taken with a pinch of salt.

The Trinity is one of the distinctive doctrines of Christianity. It goes hand in hand with the doctrine of the Incarnation, since if Jesus Christ was God, and at the same time the Son of God, there must be a distinction between God and God. The implications were worked out several centuries after the resurrection and ascension of Christ, giving Unitarians the opportunity to argue that the doctrine was a mere human invention. I think it can be shown that Scripture does imply and even teach the Christian Trinity. But does the doctrine make sense, metaphysically? As I wrote previously, the Sufi author of The Transcendent Unity of Religions, Frithjof Schuon, does not think so.

Schuon writes in Christianity/Islam (p. 97): “what Islam blames Christianity (not the Gospels) for is not that it should admit of a Trinity within God, but that it should place this Trinity on the same level as the divine Unity; not that it should attribute to God a ternary aspect, but that it should define God as triune, which amounts to saying either that the Absolute is triple or else that God is not the Absolute.”

But if this is what Islam thinks, then Islam blames Christianity for a sin it does not commit. The Church teaches that the Absolute is both One and Three, but not in the numerical sense, not “triple”, as if one could place the three Persons side by side and count them. As Meister Eckhart writes in his Commentary on Exodus, “God is one, outside and beyond number, and is not counted with anything”, and adds that in the Godhead “the same essence and the same act of existence which is the Paternity is the Sonship: the Father is what the Son is. Nevertheless, the Father himself is not the Person who is the Son, nor is the Paternity the Sonship.” Eckhart’s teaching is implied in this simple statement by St Augustine, cited by Joseph Ratzinger in his classic Introduction to Christianity (p. 183): “He is not called Father with reference to himself but only in relation to the Son; seen by himself he is simply God.” The Trinity is not a view of God from the outside – despite its symbolic depiction in Christian art – but is a secret of his interior life, of his relations with himself.

Islam’s inability to grasp all this is, of course, perfectly understandable. It cannot be grasped. We cannot “know” the Trinity, for the Trinity itself is something we can only accept in faith as Eckhart did, by assenting to the revelation of the Word. If a Muslim assented to that revelation, he would become a Christian. We can never get “outside” the Trinity in order to grasp it as an object. It is within the Trinity that we ourselves are grasped and understood, and “then I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood” (1 Cor. 13:12), but not otherwise.

If you like, read my "Face to Face: The Difference Between Christian and Hindu Non-Dualism".

The Trinity is one of the distinctive doctrines of Christianity. It goes hand in hand with the doctrine of the Incarnation, since if Jesus Christ was God, and at the same time the Son of God, there must be a distinction between God and God. The implications were worked out several centuries after the resurrection and ascension of Christ, giving Unitarians the opportunity to argue that the doctrine was a mere human invention. I think it can be shown that Scripture does imply and even teach the Christian Trinity. But does the doctrine make sense, metaphysically? As I wrote previously, the Sufi author of The Transcendent Unity of Religions, Frithjof Schuon, does not think so.

Schuon writes in Christianity/Islam (p. 97): “what Islam blames Christianity (not the Gospels) for is not that it should admit of a Trinity within God, but that it should place this Trinity on the same level as the divine Unity; not that it should attribute to God a ternary aspect, but that it should define God as triune, which amounts to saying either that the Absolute is triple or else that God is not the Absolute.”

But if this is what Islam thinks, then Islam blames Christianity for a sin it does not commit. The Church teaches that the Absolute is both One and Three, but not in the numerical sense, not “triple”, as if one could place the three Persons side by side and count them. As Meister Eckhart writes in his Commentary on Exodus, “God is one, outside and beyond number, and is not counted with anything”, and adds that in the Godhead “the same essence and the same act of existence which is the Paternity is the Sonship: the Father is what the Son is. Nevertheless, the Father himself is not the Person who is the Son, nor is the Paternity the Sonship.” Eckhart’s teaching is implied in this simple statement by St Augustine, cited by Joseph Ratzinger in his classic Introduction to Christianity (p. 183): “He is not called Father with reference to himself but only in relation to the Son; seen by himself he is simply God.” The Trinity is not a view of God from the outside – despite its symbolic depiction in Christian art – but is a secret of his interior life, of his relations with himself.

Islam’s inability to grasp all this is, of course, perfectly understandable. It cannot be grasped. We cannot “know” the Trinity, for the Trinity itself is something we can only accept in faith as Eckhart did, by assenting to the revelation of the Word. If a Muslim assented to that revelation, he would become a Christian. We can never get “outside” the Trinity in order to grasp it as an object. It is within the Trinity that we ourselves are grasped and understood, and “then I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood” (1 Cor. 13:12), but not otherwise.

If you like, read my "Face to Face: The Difference Between Christian and Hindu Non-Dualism".

Illustration: Holy Trinity, by Luca Rossetti da Orta, 1738-9, from Wikimedia.

Thursday, 28 April 2011

More on the Resurrection Body

Why did the wounds on Christ’s body still appear after the Resurrection? A wound, if you think about it, is an occasion when what is within us is exposed, where the life-blood has been poured out. In Christ’s case, what is within him is love, is the Holy Spirit. The places where human sins inflicted pain on him are the very places where, because that pain was accepted on our behalf and for our sake, Christ’s love was most fully expressed. The wounds are the ways he reaches out to us, invites us into his body; they are ways he shares his blood with us. So those wounds were not just forensic evidence that he was the same person who had suffered, nor mere trophies reminding us of his victory over death, but – according to a widespread mystical tradition – a place for sinners to take refuge. That is, the signs of vulnerability in his physical body remain places of vulnerability in a spiritual sense, places where he may be approached and entered into.

Something similar applies to psychological wounds, which of course cut much deeper than physical ones, and many of which are inflicted in childhood. But Christ had a happy childhood – one might almost say a sheltered one (after the escape from Herod). He was held in the arms of Mary and Joseph, nourished, affirmed, educated. How could he know the psychological suffering that stems from being abused or neglected at an early age by those who ought to love you but don’t?

We know that he accepted the punishment for sins he did not commit – which means the pain that comes from having sinned even though he never did. It must be that he experienced in his Passion at least a taste of every sin, of every punishment, when he was tortured, abused, and scorned, when he carried his cross, or felt abandoned by his Father, or knew himself to be deserted and betrayed by his friends. In order to heal the consequences of every sin throughout history, he had to “assume” them or take them into himself, as he took human nature into himself.

We make the mistake of thinking that because he was just one man, he was a fragment of the whole, of mankind, in the same way that each of us are. The mystics say something different. They say that though he was one man, he was also the whole in which all the parts participate, so that we can each find ourselves in him. When he rises from the dead, he brings us with him, though we follow later. The wounds in our nature do not separate us from him, because they are in him too.

Illustration (Wikimedia Commons): The Incredulity of Thomas, 1268, from the Romkla Gospels.

Something similar applies to psychological wounds, which of course cut much deeper than physical ones, and many of which are inflicted in childhood. But Christ had a happy childhood – one might almost say a sheltered one (after the escape from Herod). He was held in the arms of Mary and Joseph, nourished, affirmed, educated. How could he know the psychological suffering that stems from being abused or neglected at an early age by those who ought to love you but don’t?

We know that he accepted the punishment for sins he did not commit – which means the pain that comes from having sinned even though he never did. It must be that he experienced in his Passion at least a taste of every sin, of every punishment, when he was tortured, abused, and scorned, when he carried his cross, or felt abandoned by his Father, or knew himself to be deserted and betrayed by his friends. In order to heal the consequences of every sin throughout history, he had to “assume” them or take them into himself, as he took human nature into himself.

We make the mistake of thinking that because he was just one man, he was a fragment of the whole, of mankind, in the same way that each of us are. The mystics say something different. They say that though he was one man, he was also the whole in which all the parts participate, so that we can each find ourselves in him. When he rises from the dead, he brings us with him, though we follow later. The wounds in our nature do not separate us from him, because they are in him too.

Illustration (Wikimedia Commons): The Incredulity of Thomas, 1268, from the Romkla Gospels.

Tuesday, 26 April 2011

Sherrard's critique of Rene Guénon

The late Philip Sherrard, a Perennialist and member of the Greek Orthodox Church, devotes a long chapter in his last book, Christianity: Lineaments of a Sacred Tradition, to the “Logic of Metaphysics in René Guénon” – although the points he makes are just as applicable to Schuon, as we shall see. Guénon did more than anyone else to reawaken metaphysical perception in our century, Sherrard says. But he made two important assumptions that predisposed him against Christianity and towards Vedanta (and which help to explain his own conversion from Catholicism to Islam). The first of these assumptions was that a strict correlation must be preserved between the metaphysical and the logical order – thus ruling out in advance the more paradoxical Christian relationship between Unity and Trinity in the Godhead. The second assumption was that every “determination” of the Absolute must be some form of limitation, and is therefore incompatible with the divine nature. These two assumptions led Guénon into an apophaticism so radical that he could affirm nothing at all of the Absolute, except by way of negation – including, obviously, a negation of the Christian Trinity.

Before his death, then, Sherrard had come to the conclusion that a Christian thinker who accepts Revelation must start from an entirely different point of view – must begin, in fact, from the knowledge that the supreme Principle is the Trinity, and furthermore that “personality” (indeed, triple Personality) in God is not necessarily a limitation. Without it, in fact, the Absolute has no actual freedom to determine itself or create a world: the freedom of God becomes merely the absence of external constraint. Although Sherrard assumes Schuon’s “transcendental unity” approach throughout his book, this insight calls into question one of Schuon’s core teachings: that a personal (or Tri-Personal) deity derives from an impersonal Godhead and will be “dissolved” in the gnosis which transcends Being. (As Sherrard writes, “This view thus involves a total denial of the ultimate value and reality of the personal. It demands as a condition of metaphysical knowledge a total impersonalism – the annulment and alienation of the person.”)

Sherrard’s insight leaves the other religions intact. It even leaves open the possibility that the perennialists have correctly understood them. But it separates Christianity, and perhaps even raises Christianity above them, in a way that seems to me incompatible (more so than he himself realized) with the theory of “transcendental unity” as stated by Schuon. Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, for one, believes that what Christians have to say is not something less than, say, Vedanta or Sufism, but more. In fact “the Christian is called to be the guardian of metaphysics for our time”. Of one exemplary Christian mystic he writes: “Looking into his own ground, Jan van Ruysbroeck sees beyond it into the eternal I, which for man is both the source of his own I as well as his eternal Thou, and in the final analysis this is because the eternal I is already in itself I and Thou in the unity of the Holy Spirit” [Glory of the Lord, V, p. 70]. The encounter with God in this “ground” is a nuptial encounter, a spiritual marriage. Thus “The pantheistic tat tvam asi, which identifies subject and object in their depths, can be resolved only by virtue of the unity between God and man in the Son, who is both the ars divina mundi and the quintessence of actual creation (see Book III of Nicolas of Cusa’s [De] Doctor Ignorantia), and by virtue of the Holy Spirit, who proceeds from this incarnate Son in his unity with the Father” [GL, I, 195].

Before his death, then, Sherrard had come to the conclusion that a Christian thinker who accepts Revelation must start from an entirely different point of view – must begin, in fact, from the knowledge that the supreme Principle is the Trinity, and furthermore that “personality” (indeed, triple Personality) in God is not necessarily a limitation. Without it, in fact, the Absolute has no actual freedom to determine itself or create a world: the freedom of God becomes merely the absence of external constraint. Although Sherrard assumes Schuon’s “transcendental unity” approach throughout his book, this insight calls into question one of Schuon’s core teachings: that a personal (or Tri-Personal) deity derives from an impersonal Godhead and will be “dissolved” in the gnosis which transcends Being. (As Sherrard writes, “This view thus involves a total denial of the ultimate value and reality of the personal. It demands as a condition of metaphysical knowledge a total impersonalism – the annulment and alienation of the person.”)

Sherrard’s insight leaves the other religions intact. It even leaves open the possibility that the perennialists have correctly understood them. But it separates Christianity, and perhaps even raises Christianity above them, in a way that seems to me incompatible (more so than he himself realized) with the theory of “transcendental unity” as stated by Schuon. Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, for one, believes that what Christians have to say is not something less than, say, Vedanta or Sufism, but more. In fact “the Christian is called to be the guardian of metaphysics for our time”. Of one exemplary Christian mystic he writes: “Looking into his own ground, Jan van Ruysbroeck sees beyond it into the eternal I, which for man is both the source of his own I as well as his eternal Thou, and in the final analysis this is because the eternal I is already in itself I and Thou in the unity of the Holy Spirit” [Glory of the Lord, V, p. 70]. The encounter with God in this “ground” is a nuptial encounter, a spiritual marriage. Thus “The pantheistic tat tvam asi, which identifies subject and object in their depths, can be resolved only by virtue of the unity between God and man in the Son, who is both the ars divina mundi and the quintessence of actual creation (see Book III of Nicolas of Cusa’s [De] Doctor Ignorantia), and by virtue of the Holy Spirit, who proceeds from this incarnate Son in his unity with the Father” [GL, I, 195].

Sunday, 24 April 2011

The Resurrection Body

He is risen! Death, entropy, time no longer have any dominion over him. But what does that mean?

He appeared to Mary and the other disciples, but at first they did not recognize him. He could come and go through closed doors, cook and eat fish, ascend into heaven. His body was marked by the wounds of the Cross. The powers we attribute to Superman and the other comic book heroes, the powers we would love to have – flight, X-ray vision, invulnerability, and the rest – are merely shadows of what we will experience in the resurrection, when we are joined to Christ and live in his world.

There is something dreamlike about the accounts of the resurrection, and yet also a kind of crisp realism, a dewy morning freshness. Resurrection is a bit like waking up, but it is also like having a vision or veridical dream. The world of the resurrection body, the resurrection earth, is closely related to the world of the Angels among whom we will then live, called in medieval writings the aevum or aeviternity, the “world without end”. It is in dreams that we come closest to it, especially in the dreams we call “visions” because they seem more real, looking back on them, than waking life.

St Paul tells us that our bodies will be changed, and indeed the matter of which we have been composed in this life can never be reassembled, since it changes from moment to moment and year to year. It will be converted into something new. The principle of continuity that makes us the same person is the soul which gives form to whatever matter lies at its disposal. The body that dies is like a seed – “a bare kernel, perhaps of wheat of some other grain”; “But God gives it a body as he has chosen,” “It is sown a physical body, it is raised a spiritual body,” for “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God” (1 Cor. 15: 37, 38, 44, 50).

That is why we venerate the relics of the saints – not out of some morbid fascination with skulls, or a belief in the magical properties of holy bones. The dead bodies of the saints are the seeds of the new heavens and the new earth. It is their bones that will be transformed first: this is the place where the resurrection will happen. Read Ezekiel 37: 1-6. “Thus says the Lord God to these bones: Behold, I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live.”

He appeared to Mary and the other disciples, but at first they did not recognize him. He could come and go through closed doors, cook and eat fish, ascend into heaven. His body was marked by the wounds of the Cross. The powers we attribute to Superman and the other comic book heroes, the powers we would love to have – flight, X-ray vision, invulnerability, and the rest – are merely shadows of what we will experience in the resurrection, when we are joined to Christ and live in his world.

There is something dreamlike about the accounts of the resurrection, and yet also a kind of crisp realism, a dewy morning freshness. Resurrection is a bit like waking up, but it is also like having a vision or veridical dream. The world of the resurrection body, the resurrection earth, is closely related to the world of the Angels among whom we will then live, called in medieval writings the aevum or aeviternity, the “world without end”. It is in dreams that we come closest to it, especially in the dreams we call “visions” because they seem more real, looking back on them, than waking life.

St Paul tells us that our bodies will be changed, and indeed the matter of which we have been composed in this life can never be reassembled, since it changes from moment to moment and year to year. It will be converted into something new. The principle of continuity that makes us the same person is the soul which gives form to whatever matter lies at its disposal. The body that dies is like a seed – “a bare kernel, perhaps of wheat of some other grain”; “But God gives it a body as he has chosen,” “It is sown a physical body, it is raised a spiritual body,” for “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God” (1 Cor. 15: 37, 38, 44, 50).

That is why we venerate the relics of the saints – not out of some morbid fascination with skulls, or a belief in the magical properties of holy bones. The dead bodies of the saints are the seeds of the new heavens and the new earth. It is their bones that will be transformed first: this is the place where the resurrection will happen. Read Ezekiel 37: 1-6. “Thus says the Lord God to these bones: Behold, I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live.”

Saturday, 23 April 2011

The souls in prison